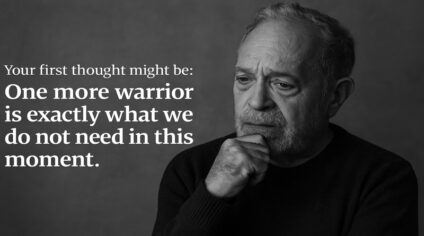

Warriors for Justice: A Stoic Response to Robert Reich

This reflection is part of the ongoing “Stoicism Journey” series, which explores how ancient Stoic principles can offer clarity, strength, and moral direction in today’s world. Each piece connects Stoic thought to real-life challenges, often intersecting with faith, justice, and the pursuit of a meaningful life. In this installment, we respond to a story shared by Robert Reich, considering what it means to be a warrior for justice in dishonorable times.

Former U.S. Treasury Secretary Robert Reich recently shared a story that cuts through the fog of despair surrounding our political moment. He wrote about a friend who defends immigrants. Someone who, despite daily encounters with cruelty and hardship, radiated calm and strength. Her secret? “I’m fighting on the front line,” she said. “And that puts you in a good place.”

Reich had expected grief or exhaustion, but instead found something close to joy. “You’re a warrior,” he told her. She agreed. And in that exchange, Reich illuminated something many people overlook: that living with moral purpose in the face of injustice can be deeply energizing. It does not drain us. It sustains us.

The idea that meaningful action in service of justice can produce not bitterness but resilience and even joy resonates with Stoic philosophy. Ancient Stoics would not have used the word “warrior” in quite the same way. Still, they too believed that the fight for virtue, especially in the face of tyranny and injustice, was the noblest of all endeavors.

At first glance, Stoicism can seem austere or passive. “Bear and forbear,” wrote Epictetus. But look closer and you find not retreat but resolve. Marcus Aurelius, Roman emperor and Stoic philosopher, understood the grind of power and politics, but still wrote in Meditations: “Waste no more time arguing about what a good person should be. Be one.”

That is the core of what Reich’s story captures. To be a good person is not to be neutral; it is to be actively engaged. It is to act, and to act rightly, even when the odds are against you.

The Stoics believed in arete, or moral excellence, as the only true good. Wealth, power, reputation, and even health were considered “indifferents.” They might be preferable, but they are not what gives life meaning. What matters is whether we live with wisdom, courage, justice, and self-discipline. That is what defines a life well-lived.

Reich’s friend lives up to that standard. She does not ignore suffering. She chooses to face it and to stand between vulnerable people and the machinery of cruelty. Not because it is easy, but because it is right. And in that stance, she finds joy. Not some fleeting kind that depends on circumstances, but a deep, durable kind that comes from living in alignment with one’s values.

Seneca, another great Stoic, once wrote, “Difficulties strengthen the mind, as labor does the body.” He was not glorifying suffering. He was naming the paradox at the heart of Stoic thought: that hardship, approached with integrity, becomes a forge for the soul. The pain of the moment becomes the proving ground for our character.

Importantly, the Stoics were not indifferent to injustice. They argued that justice was a cardinal virtue and that we are all part of a greater whole. They called this concept oikeiosis, the idea that we are not isolated individuals but members of an interdependent human family. Marcus Aurelius wrote, “What brings no benefit to the hive brings none to the bee.” We thrive only when we act with care toward others.

This ethic of shared responsibility finds a powerful echo in the Wesleyan tradition. John Wesley once said, “Do all the good you can, by all the means you can, in all the ways you can, to all the people you can, as long as ever you can.” For Wesley, faith without action was hollow. The love of God demands love of neighbor. And love of neighbors requires standing up for the dignity of every human being, especially the poor, the marginalized, and the oppressed.

This shared sense of moral duty, found in both Stoicism and Wesleyan theology, insists that our lives are not just about personal peace; they are about using our freedom and agency to act on behalf of others. Both traditions reject apathy and demand courage.

Robert Reich, who has spent decades warning about inequality, authoritarianism, and the erosion of democratic norms, often says that despair is not an option. “The only way we can make progress,” he once wrote, “is by joining together and fighting for what we believe in.” He understands that politics is not just about elections but is about the moral health of a nation. And moral health requires moral action. In Reich’s story, the friend who defends immigrants is not disconnected from pain. She is immersed in it. But she chooses to respond with strength. Her fight puts her in a “good place,” not because it is pleasant, but because it is meaningful.

Robert Reich, who has spent decades warning about inequality, authoritarianism, and the erosion of democratic norms, often says that despair is not an option. “The only way we can make progress,” he once wrote, “is by joining together and fighting for what we believe in.” He understands that politics is not just about elections but is about the moral health of a nation. And moral health requires moral action. In Reich’s story, the friend who defends immigrants is not disconnected from pain. She is immersed in it. But she chooses to respond with strength. Her fight puts her in a “good place,” not because it is pleasant, but because it is meaningful.

Massimo Pigliucci, a philosopher and advocate of modern Stoicism, argues that Stoic principles are tools for civic engagement. He reminds us that Stoicism is not about escaping the world, but about engaging with it with integrity. “The point,” he writes, “is not to hide from society, but to participate in it as an agent of virtue.”

This is where Wesleyan theology enriches the conversation once again. Methodists have a long tradition of organizing for social change. From abolition to civil rights to public health, Wesleyan practice has called people of faith into the public square. “Social holiness,” in the Wesleyan vocabulary, means that personal faith must be lived out through public responsibility.

Justice is not a distraction from the Christian life. It is one of its central expressions. Being on the front line, as Reich’s friend described, is not limited to large protests or high-profile advocacy. It may mean organizing a local food drive and calling your representatives. Challenging discriminatory policies at work or school. Helping register voters, or simply refusing to be silent in the face of cruelty.

The Stoic does not expect to win every battle. Epictetus taught that we control our actions, not their outcomes. What we can and must control is whether we act at all. “First say to yourself what you would be,” he said, “and then do what you have to do.”

We are not called to success. We are called to faithfulness. That principle is held in both Stoic and Wesleyan traditions. And in a political moment full of cruelty, where compassion is often mocked and power abused, choosing to live with moral clarity is itself a radical act. Reich urges us not to retreat into despair, but to stand up with joy and determination. This is not naïve optimism, but the clear-eyed joy of agency. It is the kind of joy found in people who know they are living in alignment with their conscience. It is joy rooted in resistance to injustice and the dignity of others.

And yes, that alignment often makes us warriors. Not warriors for domination, but for dignity. Not for conquest, but for conscience. The Stoic warrior stands because the fight itself is an expression of who they are. “To stand up straight, not straightened,” wrote Marcus Aurelius. That is the Stoic posture. Not to be bent or broken by cruelty, but to stand with quiet courage in the middle of it. There is meaning in that. There is strength in that. And there is, perhaps most surprisingly, a joy in that.

So we fight. Calmly. Clearly. Courageously. Not to win every skirmish, but to live in a way that honors what is best in us and in others. Because that, too, is the very best place.

This essay continues our journey through Stoic thought, where courage, justice, and inner discipline are not abstract ideals but living commitments. As we reflect on what it means to act with integrity in a broken world, may we find, like Reich’s friend, that we are in a “good place” when we live in alignment with our values. Future entries in the Stoicism Journey series will explore more voices and practices that help us stand up straight, not straightened.

Pingback:Deep Something | Stoic Practices: Role Models