A Way Out of No Way: John Lewis and the Moral Will

Five years have passed since Representative John Lewis died of pancreatic cancer at the age of 80. The date may have slipped past unnoticed by many. It did not go unmarked by historian Heather Cox Richardson, who opened her July 18 letter with a remembrance of Lewis and a brief recounting of the violence he endured, the justice he pursued, and the moral imagination he brought to American public life.

She included one of his final interviews, when journalist Jonathan Capehart asked what Lewis would say to those who had already given their all and still saw no change. Lewis answered with a clarity that seems forged in the crucible of history: “You must be able and prepared to give until you cannot give any more. We must use our time and our space on this little planet that we call Earth to make a lasting contribution, to leave it a little better than we found it, and now that need is greater than ever before.”

That sentiment, spoken plainly and without adornment, carries a weight that transcends its political context. Beneath the steady cadence of Lewis’s voice, one can hear the echo of an older tradition —a discipline not of strategy but of the soul.

Though Lewis drew his inspiration from Christian theology, the Civil Rights Movement, and the Black church, the moral framework in which he lived and led carries unmistakable resonance with Stoic philosophy, as well as with core teachings from Judaism, Islam, and Buddhism. His was a mind that grasped the common dignity of all people and a will that refused to be ruled by bitterness, violence, or despair. That combination, an inner resilience bound to an outer ethic, is as close to the Stoic ideal as one is likely to find in modern public life.

Lewis is most widely remembered for his call to get into “good trouble, necessary trouble.” It is a phrase now inscribed in murals and campaign slogans, but its meaning can still pierce if we allow it to. Lewis did not mean disruption for its own sake. He meant the kind of trouble one invites by standing firm in the presence of injustice.

He meant Selma. He meant lunch counters. He meant prison cells, fractured skulls, and election losses. He meant the willingness to suffer without surrendering to hate. In Stoic language, this is andreia, or moral courage, not recklessness, but the bravery to act in alignment with virtue, regardless of the outcome.

There are figures in classical Stoicism who embodied this: Cato the Younger, who chose death over submission to tyranny; Epictetus, who taught that the only real freedom lies in mastering one’s own responses; Marcus Aurelius, who bore the crushing weight of empire while striving daily to be just. Yet even these exemplars feel distant, as if their world and ours were separated by more than time.

Lewis brings that same moral vision forward from a history we can still touch. He absorbed beatings and arrests without ever surrendering to cynicism. He fought for what he believed with a fierceness that never lost its gentleness. And he never let the world harden him into its own image.

That refusal to be hardened is not a form of passivity. It is discipline. When Lewis said, “You must be able and prepared to give until you cannot give any more,” he was not preaching martyrdom. He was naming a reality: that moral labor often yields no visible results. That change is slow, sometimes generational, and the task is not to win but to be faithful.

This is where the Stoic and the prophetic traditions meet, in the unshakable commitment to do what is right even when the cost is high and the reward uncertain.

This same principle appears in Jewish thought, where the tikkun olam, repair of the world, is a calling that may never be completed, but must not be abandoned. In Christian theology, it finds form in Paul’s admonition to “run with perseverance the race marked out for us.” The Qur’an speaks of those “who enjoin what is right and forbid what is wrong, and remain steadfast through adversity.” In Buddhism, the Bodhisattva path calls one to endure suffering out of compassion for others, without attachment to the fruit of one’s actions.

These traditions, each in their own tongue, commend the practice of moral perseverance. John Lewis lived that practice. His life was one of long obedience, held together by principle.

What gives Lewis’s beliefs such enduring moral gravity is not just their consistency, but their place at the intersection of these great traditions. He stood within a specific historical struggle, but the values he lived by—courage, mercy, discipline, justice—speak across religious and philosophical boundaries. That convergence deepens the authority of his example. It reminds us that moral clarity is not the property of any single creed, but a universal call answered by the few who are willing to live it fully.

That principle was not joyless. A year before his death, Lewis sent a message that still circulates: “Do not get lost in a sea of despair. Do not become bitter or hostile. Be hopeful, be optimistic. Never, ever be afraid to make some noise and get in good trouble, necessary trouble. We will find a way to make a way out of no way.”

That final phrase, “a way out of no way,” belongs as much to the Black church as to any philosophical school. It names something both mystical and practical: the capacity to endure, to resist, to imagine freedom in the face of every force designed to crush it.

The Stoics would have understood the sentiment, if not the phrasing. Their central teaching was that external circumstances do not determine a life’s worth; only the quality of one’s choices does. One cannot control the state, the mob, or the body’s decline. But one can remain just. One can speak the truth. One can live following reason and love and refuse to be turned into an oppressor. That, too, is a way out of no way.

The American system was not built for John Lewis to succeed. It was built to erase him. But history records the opposite. The son of sharecroppers who taught himself to preach to chickens grew into a man who stood on the front lines of one of the nation’s greatest moral reckonings.

The American system was not built for John Lewis to succeed. It was built to erase him. But history records the opposite. The son of sharecroppers who taught himself to preach to chickens grew into a man who stood on the front lines of one of the nation’s greatest moral reckonings.

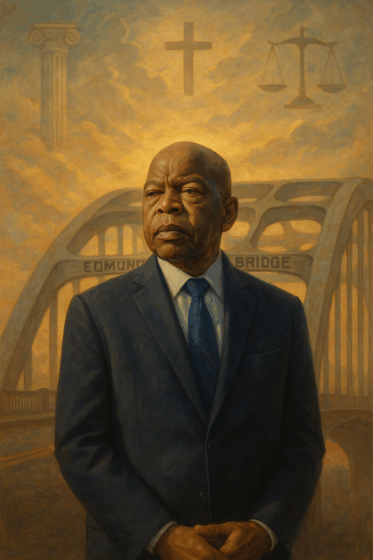

He was the youngest speaker at the March on Washington. He crossed the Edmund Pettus Bridge knowing he would be met with violence. He served in Congress for over three decades. He became not only a symbol of justice but a practitioner of it. Through it all, he remained remarkably free from bitterness. That in itself is a triumph.

Freedom, in the Stoic view, is not secured by law or property or privilege. It is won in the soul. It is the ability to live in alignment with one’s deepest values, regardless of the cost. Lewis understood this.

“My philosophy is very simple,” he once said. “When you see something that is not right, not fair, not just, say something! Do something! Get in trouble, good trouble, necessary trouble.” He did not need elaborate systems to justify this belief. His clarity came from a life of action. He knew who he was and what he stood for.

In remembering Lewis now, we are not simply revisiting the past. We are confronting the challenge of the present. The forces he opposed—racism, authoritarianism, cruelty disguised as order—have not vanished. If anything, they have grown more sophisticated. The question is no longer what John Lewis would have done. It is whether we are willing to do it.

Lewis gave us a template, not a script. His courage was not for imitation but for inspiration. To follow his example is not to march in lockstep but to live with conviction. To give until we can give no more. To give to our time and our place. To hope, not because we are naïve, but because despair is a luxury we cannot afford.

When he passed in July 2020, Lewis left behind not a movement or a theory, but a life. It remains his greatest argument. We honor him best by continuing it. The road is long. The work is hard. The outcome is never guaranteed.

But the call is clear.

We will find a way to make a way out of no way.

Pingback:Deep Something | The Stoic Path I Didn’t Mean to Take